New works from CIIS Professor of Clinical Psychology on the Psychological Potency of Dreams

Round Table for Creative Futures

CIIS Professor Alfonso Montuori and CIIS alumna Professor Gabrielle Donnelly were curious how to combat the despair and increasingly dystopian expectations of the future, and how creativity specifically could be used to inspire hope and action.

The world feels overwhelming these days. From local to global news, there are many present causes for concern—but how do present concerns impact how we engage with the future? Experts were already weighing this question before the pandemic, but in 2020 it took on new complexity and urgency. CIIS Professor Alfonso Montuori and CIIS alumna Professor Gabrielle Donnelly were curious how to combat the despair and increasingly dystopian expectations of the future, and how creativity specifically could be used to inspire hope and action. The result is the collection Handbook for Creative Futures, featuring the work of several CIIS professors from across many departments and disciplines. Their collaboration exemplifies how integral approaches can help all readers to share their knowledge, resources, and abilities to create new possibilities. They were kind enough to take even more time out of their schedules to discuss their experience of how this book came together and what they hope readers can learn.

This book is clear that humanity’s future—or rather, our plurality of futures—depends on creativity. What was the creative process like for you in developing your own work within this larger project?

Prof. Alfonso Montuori: One of the key points we wanted to make with the book is that there has been a shift in the way creativity is understood and experienced in the U.S. It’s a move away from the idea of the lone genius towards a more collaborative, systemic view of creativity. This new view of creativity taps into a shift away from traditional American individualism. The shift is also reflected generationally, in the sense that Boomers typically think of creativity in terms of eminent individuals, whereas later generations tend to represent it in what Gabrielle [Donnelly] and I call “everyone, everywhere, everyday” creativity. The book is an example of this kind of collaborative creativity, presenting a plurality of perspectives on how we can approach the future more creatively and move out of the dystopian boxes we seem to have gotten ourselves into.

Professor Jeanine Canty: I found the topic of this book to be both intriguing and highly relevant amidst our collective crises and need for radical transformation. Creativity comes in so many forms and I was pulled to dig deeper into the emergent possibilities that the individual and collective narcissism of our times, when attended to, might lead to unexpected possibilities for change and wellbeing.

Professor Emeritus Allan Combs: As a psychologist I have been interested in creativity for many years. I am not specialized in this field, but like to keep an eye on it.

Professor Gabrielle Donnelly: Early in my doctoral academic journey, I learned about Alfonso Montuori's concept of Creative Inquiry, which frames scholarship as a creative process of integrating oneself into research, an engagement between self and the world/context. By the time I was co-editing and writing the Handbook for Creative Futures, my approach to academic inquiry was inherently a creative process, made all the better by being in good company.

Professor Nick Walker: The key to my process for writing essays and book chapters is empathic imagination. I imagine myself in the shoes of a reader who’s very new to the topic, and I ask myself how I can guide this reader step-by-step through my ideas in a way that makes it easy for them to stay with me. It’s an especially fitting process for a book like this one, because I think empathic imagination is also a vital ingredient for building good futures together.

Like all of us, you were forced to find new ways to collaborate during the pandemic, and also to experience solitude in new ways. How did the circumstances of writing shape your process or theses?

Dr. Canty: During the first year of the pandemic, I was writing a book called Returning the Self to Nature: Undoing Our Collective Narcissism and Healing Our Planet and was also on a sabbatical. The invitation to write this piece aligned well because I was entrenched in the inquiry. The pandemic, while disruptive, was also beautiful in the pause it provided from everyday routine and subscription to normality. It allowed me to wonder about wild new possibilities, even under duress. Writing and creating was grounding during such uncertainty.

Dr. Combs: Actually my program, Transformative Studies, has been an online program for many years. This being the situation, my work habits during COVID were not dramatically affected, as I work at home.

Dr. Walker: I live a peaceful monk-like existence, working from home and immersed in a routine of daily practices and extensive online collaboration, so the pandemic changed very little for me and this project fit nicely into my ongoing writing practice.

Dr. Donnelly: I graduated from the online Transformative Studies Ph.D. program at CIIS in 2017. So, even before the pandemic, I had become familiar with long-distance writing and collaborative work. With contributors to the Handbook from around the world, all our exchanges in the volume composition were virtual. Given this, it has been an absolute joy to invite chapter authors to join us for an online dialogue series we've been hosting since the spring of 2023, soon after the book was published.

Dr. Montuori: One of the recurring themes in the book is the need for a shift to a view of the world that recognizes interconnection, interdependence, and complexity. The view of the world that emerged with Modernity focused very much part vs. whole and individual vs. collective. Simplification and analysis—or breaking something you want to understand into its constituent parts in order to make sense of it—worked very well up to a point, but today we see that there are vital dimensions of existence it can’t address. This is why so many of the crises we are facing today, whether environmental, political, cultural, or economic are crises of interconnectedness, which the old worldview of analysis can’t deal with. This theme of the need for a new view of the world is throughout the book, explored and explained in different ways, and it points to the outlines of the emerging worldview and the emerging world.

This book was written, edited, and published during a time of immense global instability. What sustained you through your writing and editing process?

Dr. Walker: My daily practices of aikido, meditation, and prayer.

Dr. Combs: Really, my interest in the topic, and the invitation from Alfonso.

Dr. Montuori: My co-editor Gabrielle and I are both passionate about the topic, which of course was vital. We also felt a responsibility to each other, to the authors, and to the possibility that the book might make a difference, even a very small one to inspiring change. The book is really a first step towards the creation of the Center For Creative Futures which continue to explore much-needed ways to think and act vis-à-vis the future. The response we received from non-academics was also very heartening, because people seemed to be surprised and inspired by the possibility of thinking about the future in a new way, and that in turn inspired us to keep going.

Dr. Donnelly: One of our contributors, Zia Sardar, has been writing for over a decade about the concept of postnormal times, which he argues is defined by the characteristics of chaos, complexity, and contradictions. The global instability, pandemic, political unrest, and war shaking up the globe during the writing and editing process landed this concept in very real and immediate ways. If anything, I think it kept the book anchored in the uncertainty of our times. It kept the tensions visceral and alive between perceived oppositions like hope and fear, possibility and impossibility, utopian futures and dystopian futures. I hope it has made the book more trustworthy and honest in its responsiveness to what's happening and what's ahead.

Dr. Canty: My main fields are ecopsychology and transformative learning, and both hold the possibility for extreme disruptions in our world and how to work with these. In particular, ecopsychology directly acknowledges that our world is unravelling and unsustainability. In some ways the pandemic merely reinforced this. Both fields also support the creation of new, healthier paradigms, so in many ways I often feel ready for crisis and change.

Has assembling this book changed the way you approach your own life or your own perception of the future?

Dr. Walker: Absolutely. My writing and teaching has become much more explicitly focused on encouraging others to work toward envisioning and co-creating beautiful futures, and I touch directly on this theme in all my speaking engagements now.

Dr. Montuori: Putting the book together was quite enlightening. It’s clear that there are lots of great ideas out there, and lots of great projects pointing towards more desirable and creative futures. We don’t have to be stuck on this sad trajectory to dystopia. One point we make is that wherever you look there are people against something, but it’s relatively rare to see people be for something. Say we’re against racism or sexism, for instance. What do non-racist or non-sexist relationships and even societies look like? It’s not as simple as saying, “well, no racism or sexism, right?” We need to be much more explicit about what we’re for, and what we want a non-racist, non-sexist, egalitarian or partnership culture, to use Riane Eisler’s term, really looks like.

Dr. Canty: In terms of the essay I wrote for the book, it most certainly unlocked a train of both thought and practice that is exciting for me. It is a reminder that with sickness, healing is possible and regardless of the outcome, the important part is accepting reality and creating healthier pathways.

Dr. Combs: It was a rich experience to work on, but did not significantly change my life, or my perception of the future.

Dr. Donnelly: My early years were shaped inside a community with an apocalyptic vision for the future. As an adult, I've wondered why people and groups seek certainty in an unknowable future (doomsday or rapture). This tendency can also show up subtly, and I'm fascinated by the perceived opposition between pessimism and optimism as orientations to the future. Editing and writing this Handbook was an opportunity to play with and trouble this opposition generatively. I've learned much from our brilliant contributing authors and the vantage points they bring to the conversation.

What advice would you offer CIIS students in eschewing the binary of a “hopeless/hopeful” future in favor of creating their own collaborative futures?

Dr. Canty: No matter how challenging our personal and collective crises appear, we hold massive privilege in having the opportunity to learn, practice, and create. When we come together in various collectives, in collaboration with all sentient beings, both seen and unseen, anything is possible.

Dr. Montuori: There’s a problem if hope and optimism are seen as “everything is going to be ok, don’t worry.” There’s no guarantee at all everything is going to be ok. Being hopeless is also a problem, I think. It’s giving up, and we shouldn’t give up. The issue is not “will some external force make sure everything is ok or is destroy everything.” The issue is “what can I do, with others, to contribute to inspiring hope in humanity and in our ability to come together and address the issues we’re facing.” So many people are barraged by images of the worst humans are capable of, they lose faith in humanity. So I would reframe the hopeless/hopeful as a call to become aware of how the crumbling edifice of a dying world is messing with our minds, embrace a new worldview and a also becoming aware that in age of transformation such as ours, every action, no matter how small, contributes something, and that something could be transformative. In that sense, the book is a call for transformation by mobilizing creativity, but also becoming aware of the responsibility we have for what we are creating.

Dr. Donnelly: The lure of landing on either feeling hopeful or hopeless about the future is the seduction of having certainty about what's ahead. In this certainty, we miss what evolutionary biologist Stuart Kaufmann calls the adjacent possible. Culturally, at least in North America, we are in a time when the opportunity to reinforce cynicism and degenerative visions of the future is everywhere. In news, music, television, film, and popular culture, dystopia is having a moment. There are many good reasons for this, but it does mean the capacity for positive, creative orientations is beginning to atrophy. We hope this book is an invitation to build these generative capacities towards more desirable futures for all human and non-human beings.

Dr. Walker: Indulging in anger or despair over past and present conditions won't change them, and even fighting actively against present conditions ultimately does very little to improve things. The best way to improve present conditions is to build something better to replace them. Ask yourself every day, “What are my actions actually serving to create?”

Dr. Combs: Find your passion and seek ways to pursue it to the benefit of others.

Related News

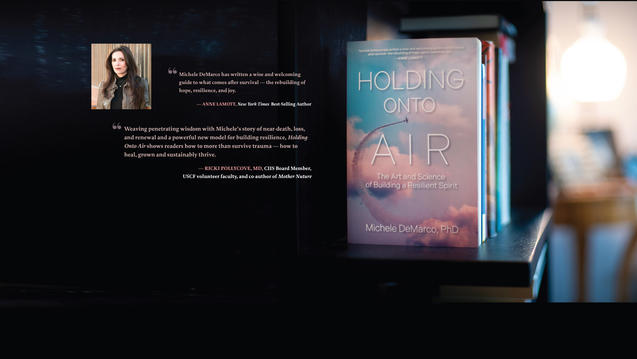

Dr. Michele DeMarco, CIIS VP for Internal Relations, Integral & Transpersonal Psychology alum, and three-time heart attack survivor, new book offers a transformative new lens for healing from trauma, grief, and loss and building resilience.

Dr. Renée Emunah, Founder and Chair of the Drama Therapy program at CIIS, reflects on the second edition of her book, Acting for Real: Drama Therapy Process, Technique, and Performance